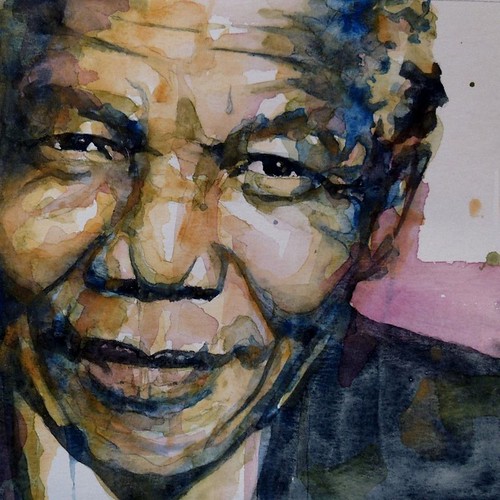

Nelson Mandela: From Prisoner to President

Nelson Mandela

1918—2013

Genesis comes to a close with the story of a prisoner who becomes president and gives a nation a future based on forgiveness. But it’s not a story which must be relegated to ancient history. These things still happen. Injustices still occur and occasionally great souls still rise up to lead people out of the dead-end of retaliation into a future only reconciliation can create. The story of a prisoner who becomes president and gives his people a future based on forgiveness is the story of the Hebrew patriarch Joseph. It’s also the story of Nelson Mandela.

The history of South Africa is one of the saddest stories in the shameful saga of European colonialism. Before the story of South Africa would give rise to hope, it would first give rise to a racist regime that lasted until the final decade of the twentieth century. After centuries of colonial exploitation, in 1948 the all-white Afrikaaner National Party instituted a government policy of segregation and discrimination based on race — a system which legally extended and institutionalized the already long existing practices of racism. The system was known as apartheid — a Dutch word meaning “separateness”. (Interestingly, the words apartheid and Pharisee both mean the same thing!)

Under apartheid only whites — 10% of the South African population — had the right to vote. Businesses, beaches, bridges, restaurants, theaters, hospitals and even ambulances were designated “Whites Only.” As part of apartheid’s brutal practices 600,000 non-whites were forcibly removed and relocated in order to enlarge “Whites Only” territory. The whole system of apartheid was designed to impoverish the black majority and enrich the white minority. Protests against racial inequality were violently crushed. Anti-apartheid activists were arrested. A typical punishment for anti-apartheid activism was public whipping. During the years of apartheid more than 40,000 blacks were “legally” subjected to the dehumanizing practice of public whipping. Others were jailed. Others were tortured. Others simply disappeared. And through it all the white only Dutch Reformed Church of South Africa assured their members that apartheid was certainly God’s will. But the wider world knew better and eventually internal activism, international condemnation and economic sanctions made apartheid untenable. In 1994 the apartheid regime was dismantled and non-white South Africans were at last given the right to vote.

The end of apartheid and the emergence of democracy in South Africa opened the door for Nelson Mandela to step onto the world stage. In 1964, at the age of forty-six, Mandela had been sentenced to life in prison as an anti-apartheid activist with the African National Congress (ANC). Released in 1990 after twenty-seven years of hard labor in a rock quarry which nearly ruined his eyesight, Nelson Mandela became the leader of the ANC. Following his release from prison, Nelson Mandela made a deliberate choice to re-enter the South African struggle without bitterness and diligently worked with President F.W. de Klerk for a peaceful transition to a democratic government. In 1993 Mandela and de Klerk were awarded the Noble Peace Prize. A year later South Africa held their first full and free democratic elections. Nelson Mandela had waited seventy-six years before he could vote and now his fellow countrymen elected him the first president of the new South Africa. The prisoner had become president. Joseph’s amazing story had been repeated. And if there were any question as to whether President Mandela would pursue a course of reconciliation or revenge, the answer was given when he invited his white jailer to be his honored guest at his presidential inauguration.

But what would the future hold for South Africa? Many assumed there would be a bloodbath of retaliation. Many assumed that now it would be time for those who had so long been denied justice to exact their revenge with violent retribution. But that didn’t happen. South Africa instead made a peaceful transition from a racist regime to a stable democracy. It was nothing short of a miracle. But how was this accomplished? It was accomplished through prophetic imagination — through daring to imagine a new and creative way of moving beyond the wrongs of the past. Not the way of exacting revenge and not the way of ignoring justice, but by the way of restorative justice; a new way which gave room for both truth and reconciliation. Nelson Mandela understood that trials similar to the Nazi war crimes trials following Word War II would rip South Africa apart. He also knew that to simply forget the injustices of the past would be a further injustice — an injustice to the truth. Instead, Nelson Mandela envisioned a third way. Not Nuremburg trials, not national amnesia, but restorative justice.

To lead the nation beyond the toxic memories of the past which had the capacity to poison the future, but to do it in a way that did not sacrifice the truth, Nelson Mandela established the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. To lead this radical new approach to addressing injustice, President Mandela appointed Anglican archbishop and fellow Nobel Peace Prize laureate Desmond Tutu as chairman of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. It was Bishop Tutu who gave the world the wonderful phrase, “There is no future without forgiveness.”

Here is the brilliance and beauty, the wisdom and grace, the imagination and creativity of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. If any person who had committed crimes under the apartheid system would make a full and public confession before the commission, they would immediately receive full amnesty for their crimes. (Unconfessed apartheid crimes remained subject to conventional criminal prosecution.) And what was the result? Over seven thousand people made their confession and received amnesty. Many of the amnesty hearings were conducted in churches. I cannot imagine a more appropriate place for truth and reconciliation to prevail and for amnesty to be given than in a church.

Another aspect of the Truth and Reconciliation project was the opportunity for victims to tell their stories — to tell the nation and the world what had been done to them in the name of apartheid. Their stories were broadcast on television and radio and printed in the newspapers. More than twenty thousand victims came forward to tell their story. As they did so they gave truth the hearing it had so long been denied. Sin was named and shamed and truth had its day. In this way justice did not become ugly retribution, which would simply set the table for the next cycle of revenge. But neither was justice denied and victims forgotten. A third way had been found. The way of truth. The way of reconciliation. The way of forgiveness. The way that could give a nation a future beyond the self-destruction of forever seeking revenge. Truth and reconciliation had danced together and neither was denied. Or as the psalmist said, “Mercy and truth have met together, righteousness and peace have kissed.”

Nelson Mandela found a way for a nation to live the Lord’s prayer. A nation was praying, “forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us.” A nation was praying, “Thy kingdom come, Thy will be done, on earth as it is in heaven.” In a very real way the kingdom of God was breaking in. Through the Jesus way of forgiveness a nation was given a future it could have no other way. This is what Amos dreamed of when he spoke of justice rolling down like water. This is, at least in part, what Jesus intended when he spoke of making disciples of the nations. Restorative justice is the kind of justice the prophets talked about. This is the kind of justice Jesus wants to bring to a broken world. This is the kind of justice that can happen when we choose to end the cycle of revenge. This is the kind of justice that can happen when we are more interested in restoration than retaliation.

God bless Nelson Mandela.

BZ

(This is an excerpt from Unconditional?)