Grain and Grape

Grain and Grape

Brian Zahnd

In the mystery of the Eucharist God in Christ chooses to make himself present to humanity by ordinary elements. Through grain and grape we find Christ present in the world. But it’s not unprocessed grain and grape that we find on the Communion table, it’s bread and wine. Grain and grape come from God’s good earth, but bread and wine are the result of human industry. Bread and wine come about through a cooperation of the human and the divine. And herein lies a beautiful mystery. If grain and grape made bread and wine can communicate the body and blood of Christ, this has enormous implications for all legitimate human labor and industry.

The mystery of the Eucharist does nothing less than make all human labor sacred. For there to be the holy sacrament of Communion there must be grain and grape, wheat fields and vineyards, bakers and winemakers. Human labor becomes a sacrament. A farmer planting wheat. A vintner tending vines. A miller grinding wheat. A winemaker crushing grapes. A woman baking bread. A man making wine. A trucker hauling bread. A grocer selling wine. Who knows what bread or what wine might end up on the Communion table as the body and blood of Christ.

This is where we discover the holy mystery that all labor necessary for human flourishing is sacred. A farmer plowing his field, a worker in a bakery, a trucker hauling goods, a grocer selling wares, all are engaged in work that is just as sacred as the priest or pastor serving Communion on Sunday. The Eucharist pulls back the curtain to reveal a sacramental world.

Don’t over-scrutinize or over-literalize this Eucharistic mystery. Don’t try to miss the point. Don’t get hung up on whether or not the labor is connected specifically with the production of grain and grape, bread and wine — the elements of Communion. That’s not the point. The point is that all work necessary for human flourishing is not just legitimate, but sacramental. Indeed we are a “kingdom of priests” and “the kingdom of the world has become the kingdom of our Lord and his Messiah.”

What we may think of as routine and mundane is actually an engagement with the sacred. The mystery of the Eucharist reveals this to be so. Annie Dillard in Holy the Firm makes this point when she tells the story of buying the communion wine for her tiny church on Puget Sound.

“How can I buy the communion wine? Who am I to buy the communion wine? Someone has to buy the communion wine. Having wine instead of grape juice was my idea, and of course I offered to buy it. Shouldn’t I be wearing robes and, especially, a mask? Shouldn’t I make the communion wine? Are there holy grapes, is there holy ground? There are no holy grapes, there is no holy ground, nor is there anyone but us. I have an empty knapsack over my parka’s shoulders; it is cold, and I’ll want my hands in my pockets. According to the Rule of St. Benedict, I should say, Our hands in our pockets. ‘All things come of thee, O Lord, and of thine own have we given thee.’ There must be a rule for the purchase of communion wine. ‘Will that be cash, or charge?’ … And I’m out on the road again walking, my right hand forgetting my left. I’m out on the road again walking, and toting a backload of God. Here is a bottle of wine with a label, Christ with a cork. I bear holiness splintered into a vessel, very God of very God, the sempiternal silence personal and brooding, bright on the back of my ribs.”

We may live in a secular age, but our secular age lives and moves and has its being in a sacramental world. Our secular eyes may be too dim to see it, but that doesn’t mean creation is not shining with the brightness of God. The light brighter than the sun on the Mount of Transfiguration testifies that flesh and blood can convey the glory of God. In our sometimes frenzied, sometimes wearied labors we can become blind to the glory that is all around us. Like the joker said to the thief,

Businessmen, they drink my wine, plowmen dig my earth

None of them along the line know what any of it is worth

–Bob Dylan, All Along The Watchtower

But the Eucharist shows us the worth! God’s good creation is holy enough to hold the life of God — whether it be a burning bush, a baby in Bethlehem, grain and grape, bread and wine. It’s not a rare diamond or a magical elixir that communicates the life of Christ to us, but something as common, earthy, and ordinary as bread and wine.

Every time we receive Communion we are reminded that we live in a sacramental world. The wheat fields of Kansas and the vineyards of California are as holy as chapels and cathedrals. God reveals himself not in inscrutable quatrains, but in grain and grape. The scent of God can be detected in the smell of a newborn baby and the sweat of a carpenter, in bread baking and wine fermenting.

Secularism is not a state of being, it’s only a way of misapprehending the world. If we walk the 21st century Emmaus road thinking God is absent and the mission has failed, we will be deeply disappointed. But if we can learn to recognize Jesus in another form and see him revealed in the breaking of bread, our hearts will burn with joy!

“O God, whose blessed Son made himself known to his disciples in the breaking of bread: Open the eyes of our faith, that we may behold him in all his redeeming work; who lives and reigns with you, in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, now and forever. Amen.” –Book of Common Prayer

BZ

This post is adapted from the “Grain and Grape” chapter in Water To Wine.

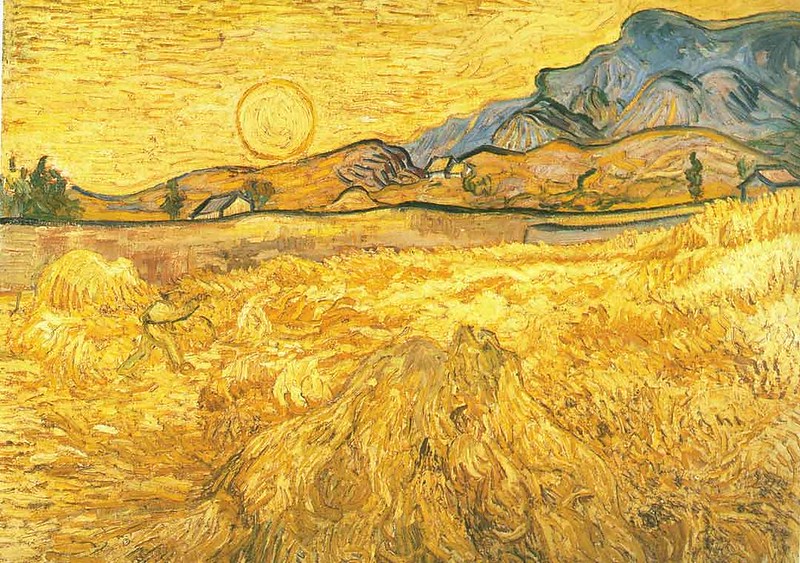

(The artwork is Wheat Field by Vincent Van Gogh, 1888)