Sympathy for the Devil…or Pilate

Brian Zahnd

Please allow me to introduce myself

I’m a man of wealth and taste

I’ve been around for a long, long year

Stole many a man’s soul and faith

And I was ‘round when Jesus Christ

Had his moment of doubt and pain

Made damn sure that Pilate

Washed his hands and sealed his fate

Pleased to meet you

Hope you guess my name

But what’s puzzling you

Is the nature of my game

–The Rolling Stones, Sympathy for the Devil

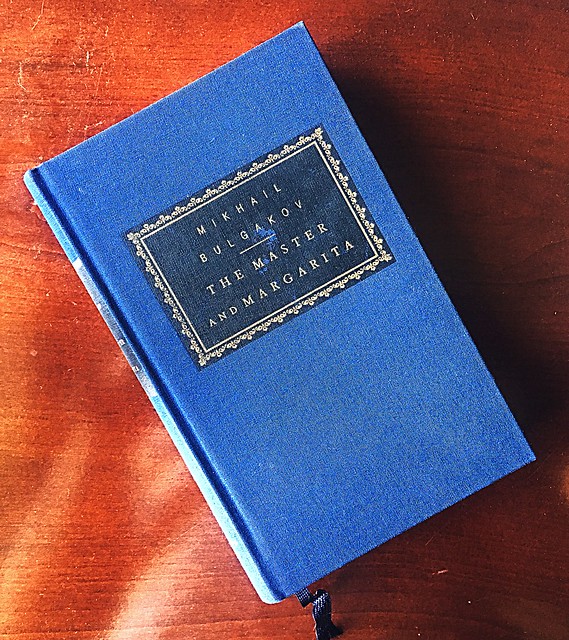

In his fascinating novel, The Master and Margarita, Russian writer Mikhail Bulgakov creates an imaginary conversation between the Roman governor Pontius Pilate and the Galilean prophet Yeshua. When asked about his views on government, Bulgakov’s Yeshua says, “All power is a form of violence over people.” The peasant preacher of Bulgakov’s novel goes on to contrast the governments of power and violence with the peaceable kingdom of truth and justice. In response Pontius Pilate rages, “There never has been, nor yet shall be a greater or more perfect government in this world than the rule of the emperor Tiberius!” When Pilate asks Yeshua if he believes this kingdom of truth will come, Yeshua answers with conviction, “It will.” Pilate cannot stand for this. In a memorable passage Bulgakov’s Pilate rails against the possibility of the kingdom of God ever coming and supplanting Caesar’s empire.

“It will never come!” Pilate suddenly shouted. Many years ago in the Valley of the Virgins Pilate had shouted in that same voice to his horsemen: “Cut them down! Cut them down!” And again he raised his parade-ground voice, “Criminal! Criminal! Criminal! Do you imagine, you miserable creature, that a Roman Procurator could release a man who has said what you have said to me? I don’t believe in your ideas!”

In The Master and Margarita, Pontius Pilate seems to have little personal animosity toward the wandering Galilean preacher, but Pilate hates his ideas. In the end what forces the Procurator to condemn Yeshua to crucifixion is the preacher’s revolutionary ideas about power, truth, and violence. Like Pilate we too wrestle with the conflict we have between Jesus and his unsettling ideas. We often want to separate Jesus from his ideas.

This bifurcation between Jesus and his political ideas has a history — it can be traced back to the early fourth century when Christianity first attained favored status in the Roman Empire. In October of 312 the Roman general Constantine came to power after winning a decisive battle in which he used Christian symbols as a fetish, placing them as talismans upon the weapons of war. (The incongruence is absolutely stunning!) Having emerged victorious in a Roman civil war and securing his position as emperor, Constantine attributed his military victory to the Christian god. In short order the wheels were set in motion for Christianity to become the state religion of the Roman Empire. The kingdom of God had been eclipsed by Christian empire.

Almost overnight the church found itself in a chaplaincy role to the empire and on a trajectory that would lead to the catastrophe of a deeply compromised Christianity. The catastrophe of church as vassal to the state would find its most grotesque expression in the medieval crusades when under the banner of the cross Christians killed in the name of Christ. The crusades are perhaps the most egregious example of how distorted Christianity can become when we separate Christ from his ideas. Read more