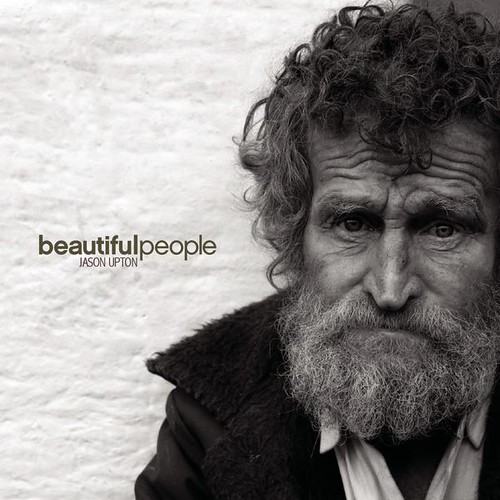

Beautiful People

Beautiful people forgive and forget.

-Jason Upton

My friend Jason Upton wrote a song about beautiful people where he told us that beautiful people forgive. I believe he’s right. If you think about it, human beings don’t do anything more beautiful than reconcile through forgiveness. We’re never more God-like, never more true to the Imago Dei, than when we forgive. Beauty and forgiveness dance together. The bottom line is forgiveness is what Christianity is mostly about. It’s why I wrote Unconditional?—a book on the call of Jesus to radical forgiveness. I wasn’t so much motivated to write a book about forgiveness as I was motivated to write about how Western Christianity (especially in the American context) has lost its way and needs to get back on track.

Forgiveness occupies the epicenter of Christian faith. If I had to choose one moment to represent the whole scope of God’s redemptive agenda from Abraham to Apocalypse, it would be Jesus upon the cross crying out, “Father, forgive them.” If any single moment can be identified as Christianity’s defining moment, that’s it! If any single text can be selected for centering our reading of the entire sacred text, it is Christ upon the cross refusing revenge in favor of forgiveness. As Swiss theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar has said—

“Being disguised under the disfigurement of an ugly crucifixion and death, Christ upon the cross is paradoxically the clearest revelation of who God is.” –Hans Urs von Balthasar, Love Alone is Credible

But have we lost sight of this? Have we lost our bearings? Have we lost our grounding center? It seems we have. And having lost the centrality of forgiveness, have we allowed Christianity to be co-opted by other agendas in which forgiveness is tangential at best? I fear this is the case. That we find ourselves in a position where the political tail is wagging the Christian dog is clear evidence that something has gone wrong. It’s not that Christianity is apolitical (it’s not!)—rather, the problem lies in partisanship producing an “us vs. them” paradigm where everything gets distorted and ugliness wins the day. The axis of partisan politics is not forgiveness, but power—and a primacy of power makes forgiveness negotiable, not unconditional. Thus evangelicalism finds itself in the lamentable state of being known for its political platform and not the practice of radical forgiveness.

What we have lost along the way is not only our central message, but our captivating beauty. The poignant beauty of Christ is seen when he sits at the table with sinners and outcasts, as he pardons those whom others would stone, as he loves his enemies even in his death. But is this what conservative Christianity is now known for? Hospitality toward secularists? Mercy for the sinner? Self-sacrificing enemy-love? Of course not. We’re known for our angry rhetoric in what we call a “culture war” and for an evangelical imitation of the shock-jock political pundits. Is it any wonder the secular world is not too interested in sitting at the Christian table?

This is why I wrote Unconditional? I didn’t set out to write a book on forgiveness, I set out to write a book on how the church can recover its beauty and authenticity. I care deeply for the health of Christianity in America and it pains me to see the evangelical church hijacked by the principalities and powers of political agenda and commercial interest. We can be so much more beautiful than this! We can embrace the cruciform! We can be Christlike! We can model enemy-love and radical forgiveness! We can find better representatives of Christianity than the televangelist doing his Rush Limbaugh impersonation. (And it doesn’t really matter if Rush is right or wrong—it’s simply not our message!) I want to reintroduce evangelical Christianity to saints like Corrie ten Boom, who forgave a Nazi concentration camp guard; Pope John Paul II, who forgave his would-be assassin; the Amish community of Nickel Mines, who forgave a child-killer and his widow; and Archbishop Nelson Mandela, who taught the world that there is no future without forgiveness. We need to reacquaint ourselves with these beautiful people.

Here’s part of the problem: Western civilization, taking Homer’s Iliad as a formative text and the avenging Achilles as the prototype for the heroic, has a hard time rejecting the “glory” of vengeance for the beauty of forgiveness. In America we especially like our cowboy justice of “make ‘em pay,” and perhaps we secretly fear that forgiveness is a kind of weakness. Certainly that’s what Nietzsche thought as he derided Christian forgiveness as nothing more than “slave morality.” Nietzsche went so far as to say that the only noble character in the New Testament was Pontius Pilate. Wow! Whatever else this tells you about Nietzsche, it certainly tells you that he had bad taste. To fail to see the transcendent beauty of Jesus Christ as compared to the cynical pragmatism of Pontius Pilate exposes a deplorable aesthetic sense! But here’s the rub—as Christians we believe Nietzsche got it wrong when he launched his bombastic attacks upon Christianity, but with our deep attraction to political machinations are we actually covert adherents of Nietzsche’s will to power? Do we secretly think that loving enemies and forgiving transgressors is actually a terrible way to go about changing the world? I wonder.

The power of Achilles or the beauty of Immanuel? In some ways, that is the choice before us. Let’s believe in the beautiful! Power certainly has a Homeric glory, but forgiveness is the essence of Christlike beauty. Achilles can valiantly avenge, but he would never forgive. And neither would Nietzsche. But to forgive is what Jesus did. And it’s beautiful. Stephen, the first Christian martyr, imitated Christ and forgave his enemies. So did Corrie ten Boom, John Paul II, the Amish, Desmond Tutu, and so many others known and unknown. These are the beautiful people. These must become our models. As long as we are more attracted to the powerful than we are to the beautiful, we will have a tragic tendency to corrupt Christianity. But things are beginning to change. Five hundred years ago change came to the church through a reformation of protest. Perhaps this time around change will come through a renaissance of beauty—the beauty of forgiveness.

BZ