The Book of Revelation

This week Group Publishing released the Jesus-Centered Bible — a study Bible in the New Living Translation. I wrote the introductions for Jonah, Matthew, Titus, and Revelation. Here’s the introduction I wrote for the book of Revelation.

The Book of Revelation

Brian Zahnd

As a child growing up in church I didn’t always feel engaged by the sermon. On those occasions I would pull out the pew Bible and begin to read. And I always went to the same place — to the end of the Bible, to the mysterious book of Revelation. I was fascinated with its monsters and battles, its angels and demons, and its visions of heaven and hell that parade across the pages in the final installment of Christian Scripture. Like many others, I assumed I was reading some kind of un-deciphered code about the end times. I thought Revelation was a veiled foretelling of the geopolitical events of the late twentieth century.

But I was mistaken.

The book of Revelation was written around the end of the first century, and is a prophetic critique of the Roman Empire. It’s a daring proclamation that Jesus Christ is the world’s new Emperor. Revelation is a wild and creative portrayal of the conflict between the beastly empire of Rome and the peaceable reign of the Lamb of God. What it foretells is the eventual triumph of the kingdom of Christ. It does this in a genre of macabre comedy — hideous monsters finally conquered by a little Lamb, a slaughtered Lamb who lives again. This is how John the Revelator tells of the triumph of Jesus over the Roman Empire and all beastly empires to come.

We must remember that everything in Revelation is told in the language of symbol. From the seven-eyed Lamb and the seven-headed dragon to the burning lake and the bejeweled city, everything is encased in symbol. But these symbols point to glorious and terrible realities. One of our challenges is that we are 2,000 years removed from the origin of these symbols. Today, if we see a cartoon of a donkey and an elephant wearing boxing gloves, we recognize it as a comic commentary on American politics. But it would likely be hard for someone 2,000 years from now to discern this political meaning. So keep in mind that most of the monstrous images in Revelation are symbols for cosmic evil working through the Roman Empire.

But it’s most important to remember what Revelation is, and what it isn’t. It’s not a coded newspaper foretelling geopolitical events of the 21st century. It is a glorious revelation of the triumph of Jesus Christ. Jesus’ lamb-like kingdom brings a saving alternative to the beast-like empires of the world. Revelation doesn’t anticipate the end of God’s good creation — it anticipates the end of violent empire.

John confessed that Jesus is Lord and Caesar is not, which is why he was exiled to the prison island of Patmos. From that deep faith there spilled forth all kinds of creative images to communicate this glorious reality: “The world has now become the Kingdom of our Lord and of his Christ and he will reign forever and ever.” (Revelation 11:15) This is the great revelation of Revelation!

BZ

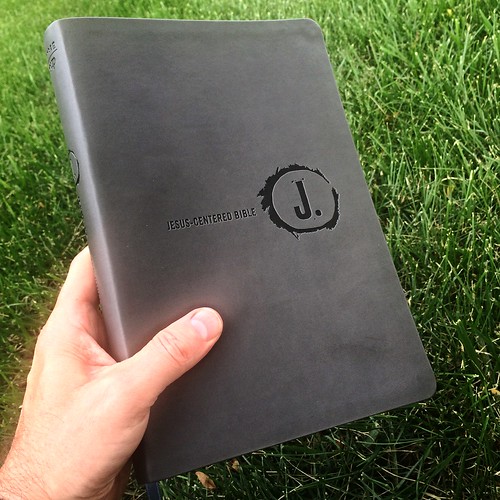

P.S. I love this Bible. New Living Translation is what I use for my devotional reading and it’s what I recommend to lay readers. (And just so you’ll know, I don’t receive any royalties from the Jesus-Centered Bible.)

My Jesus-Centered Bible.

(The artwork is the illustration of Revelation 4-5 for the Ottheinrich Bible by Matthias Gerung, 1532.)