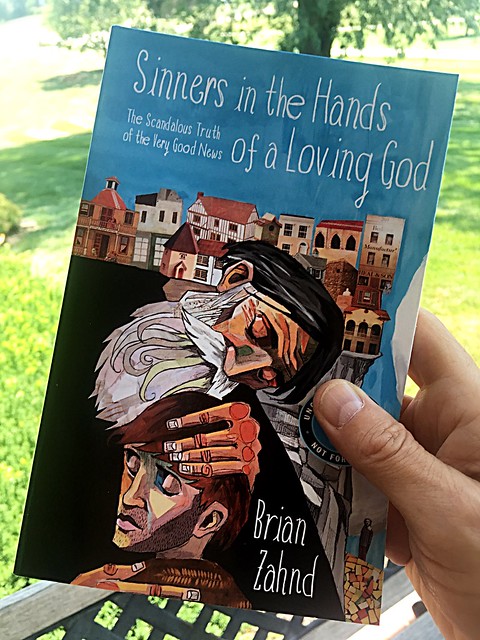

Foreword to “Sinners in the Hands of a Loving God”

Sinners in the Hands of a Loving God releases August 15. Let me share with you Wm. Paul Young’s foreword. It’s full of brilliant and beautiful insights about our journey to know the God revealed in Christ. Enjoy!

BZ

Foreword

There is a chapter in the novel, Cross Roads, which I wrote after The Shack, called “The War Within.” The war is between the head and the heart, between our experiences of the past and the present, between the false self with all the lies that have become sanctuaries and the Truth that tenderly invades its domain, between what we thought to be right and the path we seem to be travelling. Below the chapter title in the novel is the following quote:

“The Apostle tells us that ‘God is love’; and therefore, seeing he is an infinite being, it follows that he is an infinite fountain of love. Seeing he is an all-sufficient being, it follows that he is a full and overflowing, and inexhaustible fountain of love. And in that he is an unchangeable and eternal being, he is an unchangeable and eternal fountain of love.”

Part way through the chapter, the main character, Tony, finds himself in a monstrous battle. His accusers are caricatures of his own false self, liars and pretenders. They use god-language and throw back into his face his own deepest secrets. Among the language of their attack are phrases such as,

“…pour out your just and holy fury, the bow of your wrath bent and the arrow made ready on the string, and justice bending the arrow at their hearts…”

The quotes above were written by the same man, Jonathan Edwards. The fiery language of accusation was delivered in his famous sermon “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God,” and the other line was from his “Heaven, a World of Charity, or Love” in Charity and its Fruits.

What happened between a beautiful expression of a God of First Love and the jarring explosion of a vindictive being focused on retributive justice? Was this a movement or a constant tension within him?

We will never know for sure, but during his lifetime Edwards experienced significant personal losses. He changed his mind on public issues and was eventually ostracized by his own congregation. After witnessing injustice, he took a stand against slavery and became an advocate for the indigenous tribal people. Visitors would come to hear him speak, but his own people would not. Edwards knew personally about the war within.

Dr. Baxter Krueger refers to this inner tension as the windshield-wiper of the soul that vacillates between two visions of God. The first is powerful and transcendent, a God of glory or might, sitting on a distant throne wrapped in unapproachable light. While the transcendent imagination of God might inspire awe and fear, it does not generate relational embrace or ease.

But there is a second, qualitatively divergent vision of God that also attracts us. It doesn’t begin with the mind trying to grasp the immensity and grandeur of God, but the heart that yearns for beauty and the wonder of being well loved. This is the God of my deepest longings, the One whom I can taste in the rhythms of music and creativity, catch glimpses of in my encounters with love, and feel embraced in the holy encounter with an ‘other.’ This is the whisper of the Spirit and the gentle touch of love.

It should be no surprise that we are naturally attracted to both. We not only experience this flip-flop within our own soul’s journey, but this windshield-wiper effect is evident throughout Scripture. The psalmist and the prophet move back and forth, sometimes within the same verse: light and dark, good and evil, power and comfort, transcendence and immanence, faithfulness and abandonment.

Into this polarity is introduced an astounding event that reframes everything — Jesus! — the incarnation of the transcendent God directly into the deepest longings and aspirations of our humanity. In Jesus everything is brought together, all the disparate extensions of our mindful grasping after the transcendent God, and the scattered but viscerally real pursuit of an integrated and relational love with an immanent God. Both our understanding and experience of God must be grounded in our Christology. Apart from Jesus we can do, know, be nothing.

Every author writes something they later regret. Every preacher wishes they could take something back that they once delivered as truth. If transformation is by the renewal of the mind and I have never changed my mind, then be assured I am actively resisting the work of the Holy Spirit in my life. Everyone who grows, changes.

But it is hard work to change, to be open, to take the risk of trust. Change always involves death and resurrection, and both are uncomfortable. Death because it involves letting go of old ways of seeing, of abandoning sometimes precious prejudices. It means having to ask for forgiveness and humble ourselves. And resurrection is no easy process either; having to take risks of trust that were not required when everything seemed certain, agreeing with the new ways of seeing while not obliterating the people around you, some who told you what they thought was true but isn’t after all.

Transformation is not easy, ask any butterfly.

In this book, Brian Zahnd is pushing Jesus into the middle of our windshield-wiper conversations about God. This is not an exercise in being right but an invitation to know God, who we discover is a Person. Therefore, this book is about a relationship full of mystery and the loss of control, which is another way of talking about trust. As difficult as the transformation feels, the result is something almost too beautiful for words — resurrection.

—Wm. Paul Young,

author of The Shack, Cross Roads, Eve and Lies We Believe About God

(You can read the entire first chapter of Sinners in the Hands of a Loving God for free here.)