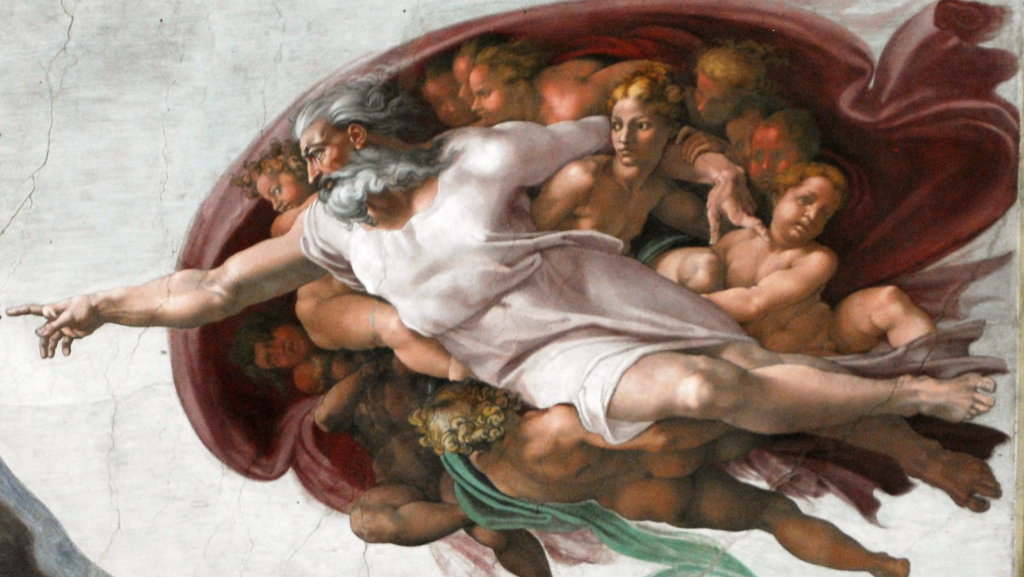

Why Did God Create the World?

Why Did God Create the World?

Brian Zahnd

I’m currently reading The Lamb of God by Sergius Bulgakov. Sergius Bulgakov (1871–1944) is widely regarded as the leading Orthodox theologian of the twentieth century. Regarding The Lamb of God, David Bentley Hart says, “This book is quite simply the most remarkable and impressive work of Christology produced in the twentieth century.”

Today I read something so beautiful I felt I had to share it. This is the first three paragraphs of the chapter entitled “The Creaturely Sophia.” This is technical academic theology that some may find a bit daunting, so at the end I’ve added a few paragraphs from my book Water To Wine in which I attempted to say something similar. My take on why God created the world is less technical and less thorough, but perhaps it’s more poetic and more accessible.

Here’s Sergius Bulgakov on why God created the world:

“God created the world out of nothing” (ex ouk onton). What is the relation of this act of the creation of the world to the proper life of God or to His eternity? “God is a totally self-sufficient and all-blessed being.” This means that God’s eternity contains the entire fullness of His life both through the disclosure of His hypostatic being (in trinitarity) and through the disclosure of His natural Divinity in the Divine Sophia. God is absolute in His proper, divine life, and He does not need the world for Himself. For Him, the creation or non-creation of the world is not a hypostatic or natural necessity of self-completion, for trihypostatizedness fully exhausts the hypostatic self-definition and closes its circle, whereas God’s nature is fullness that contains the All in itself. Thus, the necessity of creation does not flow from the proper life of Divinity and Divinity’s self-positing; there is no place for creation in Divinity itself. And in this sense, the creation of the world can only be the proper work of Divinity, not in His hypostatic nature, but in His creative freedom. In relation to the life of Divinity itself, the world did not have to be.

However, this freedom in the sense of the absence of natural or hypostatic necessity does not at all signify the presence of randomness or arbitrariness in the being of the world. One should not think that the world was in fact created according to the whim of the omnipotence, without any reason and meaning for the Creator Himself but simply as a manifestation of His power. Such a notion is blasphemous and corresponds only to Schopenhauer’s atheistic philosophy, according to which the Divine Will, at random or according to a meaningless whim, caused the world to appear. God’s freedom in the creation of the world signifies only the absence of a determinate necessity for Him as a need for Him to develop or complete Himself (a notion that is not alien to the pantheism of Schelling or Hegel). But by no means does this mean that the world is not needed by God in some other sense (besides His own self-completion) or that He could have not created the world (a notion that diminishes the grandeur of God).

God needs the world, and it could not have remained uncreated. But God needs the world not for Himself but for the world itself. God is love, and it is proper for love to love and to expand in love. And for divine love it is proper not only to be realized within the confines of Divinity but also to expand beyond these confines. Otherwise, absoluteness itself becomes a limit for the Absolute, a limit of self-love or self-affirmation, and that would attest to the limitedness of the Absolute’s omnipotence — to its impotence, as it were, beyond the limits of itself. It is proper for the ocean of Divine love to overflow its limits, and it is proper for the fullness of the life of Divinity to spread beyond its bounds. And if it is in general possible for God’s omnipotence to create the world, it would be improper for God’s love not to actualize this possibility, inasmuch, for love, it is natural to love, exhausting to the end all the possibilities of love. We therefore have one of the following possibilities: Either the creation of the world is an impossibility for God, in which case the impossibility would constitute a limit for Him, would make Him limited; or in the case of such a possibility, God’s love could not fail to actualize it by creating the world. Consequently, God-Love needs the creation of the world in order to love, no longer only in His own life, but also outside Himself, in creation. In the insatiability of His love, which is divinely satiated in Him Himself, in His own life, God goes out of Himself toward creation, in order to love outside Himself, not Himself. This extradivine being is precisely the world or creation. God created the world not for Himself but for the world. In creating it, He was moved by love that was not limited even by Divinity that poured forth outside of Him. And in this sense the world could not fail to be created.

________________________________

And here is my take from Water To Wine on why God created the world:

The Bible opens with a creation narrative, and the constant refrain is the goodness of it all. In the first chapter of Genesis God declares every day as good. The third day (the day life begins) is declared good twice. On the sixth day of creation we are told, “God saw everything that he had made, and indeed, it was very good” (Genesis 1:31). The ancient Hebrew account of the entire goodness of creation stands in stark contrast to the pagan creation stories where the world comes into existence amidst the chaos of a great struggle between good and evil. In the rival myths of the ancient world, evil plays a role in creation. The first great revelation of the Hebrew scriptures is that the universe flows entirely from the goodness of God; evil played no part in God’s good creation.

Genesis also takes us beyond where science can go. Astrophysicists can quite accurately trace the beginning of time back 13.8 billion years to the “let there be light” moment known as the Big Bang. But beyond that they cannot go. Anything prior to energy and matter (and the “time” which matter and energy create) is an impenetrable barrier for empiricism. Which is why Ludwig Wittgenstein concludes his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus by famously saying, “What we cannot speak about we must pass over in silence.” Wittgenstein understood that there can never be a purely scientific answer to this fundamental question: Why is there something instead of nothing? Any attempt to answer this grand question broaches upon the philosophical or, more accurately, the religious.

The great monotheistic faiths have always answered the question of why there is something instead of nothing in the same way, the only way it can be answered: GOD. “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth” (Genesis 1:1). But why? Why did God bother? Why did God create? Why did God say, “Let there be”? The mystics have always given the same answer — because God is love, love seeking expression. From what the Cappadocian Fathers called the perichoresis — the eternal dance that is Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, there burst forth an explosion of love. Some call it the Big Bang. Some call it Genesis. If you like we can call it the genesis of love as light and all that is. What is light? God’s love in the form of photons. What is water? A liquid expression of God’s love. What is a mountain? God’s love in granite, so much older than human sorrow. What is a tree? God’s love growing up from the ground. What is a bull moose? God’s love sporting spectacular antlers. What is a whale? Fifty tons of God’s love swimming in the ocean. As we learn to look at creation as goodness flowing from God’s own love, we begin to see the sacredness of all things, or as Dostoevsky and Dylan said, in every grain of sand. All of creation is a gift — a gift flowing from the self-giving love of God.

Why are there light and oceans and trees and moose and whales and every grain of sand? Because God is love — love that seeks expression in self-giving creativity. Unless we understand this we will misunderstand everything, and in our misunderstanding we will harm creation, including our fellow image-bearing sisters and brothers. Existence only makes sense when it is seen through the lens of love. At the beginning of time there is love. At the bottom of the universe there is love. Admittedly freedom allows for other things too — from cancer cells to atomic bombs — but at the bottom of the universe it’s love all the way down. Cancer cells and atomic bombs will not have the final word. At the end of all things there is love. When the last star burns out, God’s love will be there for whatever comes after. In the end it all adds up to love. So when calculating the meaning of life, if it doesn’t add up to love, go back and recalculate, because you’ve made a serious mistake. Love alone gives meaning to our fleeting fourscore sojourn.

“Unless you love, your life will flash by.” –The Tree of Life

BZ