The Jesus Movement Revisited

The Jesus Movement Revisited

Brian Zahnd

My friend Shane Claiborne asked me about my experience with the Jesus Movement of the 1970s, so here’s an excerpt from Postcards From Babylon where I write about it:

I began to follow Jesus during the heady days of the Jesus Movement — the Jesus-centered spiritual movement that began among counterculture young people in California, spread across the country and eventually became significant enough to be featured on the cover of Time magazine. The center of the Jesus Movement in St. Joseph, Missouri was the Catacombs — a Christian coffeehouse in the basement of a dive bar in a seedy part of town. The Catacombs was mostly a music venue for the emerging Jesus Music scene. We usually hosted local Christian artists, but occasionally nationally known artists like Keith Green, Second Chapter of Acts, and Sweet Comfort Band would play the Catacombs.

The Catacombs was an apt name for our Jesus Movement coffeehouse — it spoke both of our dingy, subterranean venue and the connection we felt to early Christianity. The catacombs in Rome are the underground labyrinths created by the early Christians for the burial of believers and occasionally for Eucharistic worship. The Roman catacombs have become a kind of symbol for pre-Constantine Christianity; a subversive underground movement challenging the idolatrous claims of empire; a dangerous counterculture society confessing that because Jesus is Lord, Caesar is not. Christians praying underground in the Catacombs and Christians martyred above ground in the Coliseum have become the two enduring icons of the Christianity that predates Christendom.

For various reasons those of us who were part of the Jesus Movement of the 1970s felt a connection with the Jesus Movement of the AD 70s. We may not have been thrown to the lions, but we had a very distinct sense that we belonged to a Christian counterculture. We liked to believe we represented a more radical version of Christianity than what you would likely find in your local Baptist or Catholic church. Sure, a lot of this was youthful naïveté with a dose of adolescent arrogance, but forty years later I can honestly say there was a grain of truth in it. We may have been young, naïve, and a bit too cocky, but we were also undeniably countercultural. We didn’t see Christianity as a form of civic religion in service of American values, but as a direct challenge to the assumed cultural values of America.

The Jesus Movement, like its secular predecessor, the hippie movement, was markedly non-materialistic. Granted it’s a lot easier to be non-materialistic when all you own is a pair of blue jeans, a couple of t-shirts, and a record collection. Those were the days before mortgages, maternity bills, and IRAs. But the point is we didn’t shy away from the jarring passages in the Gospels where Jesus says uncomfortable things like “None of you can become my disciple if you do not give up all your possessions.” (Luke 14:33)

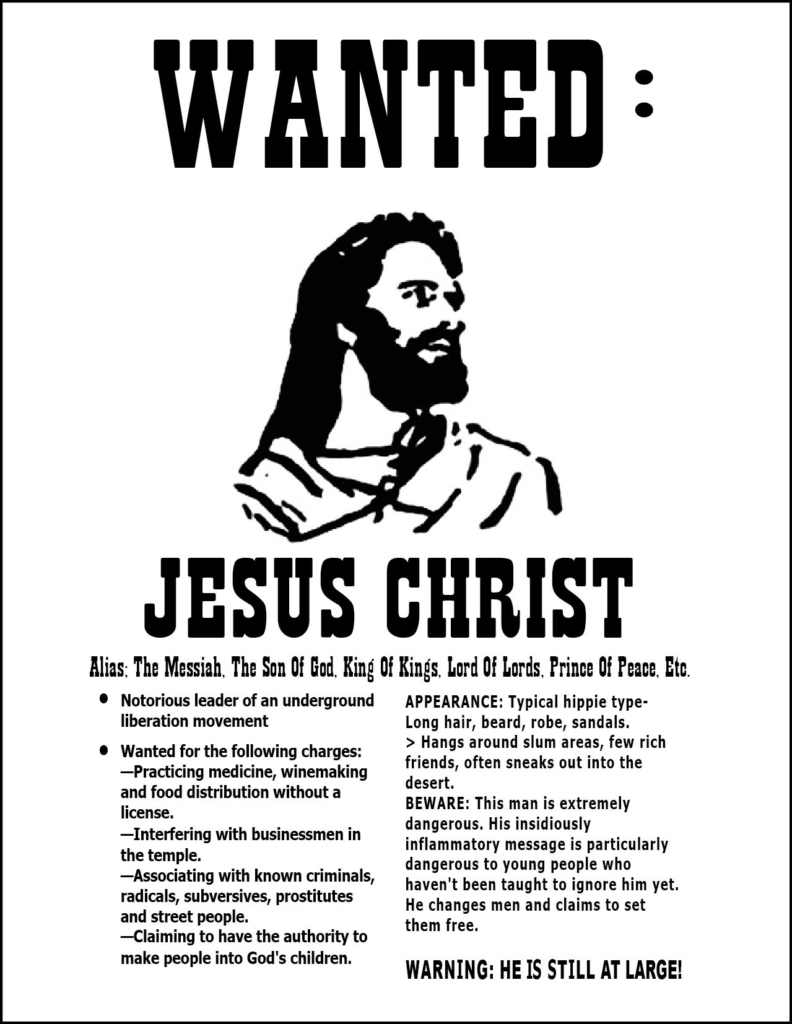

The Jesus Movement also carried a strong antiwar sentiment. We were pro-peace and antiwar, not because John Lennon sang about it in “Imagine,” but because Jesus preached about it in the Sermon on the Mount. Perhaps the best thing I can say about the Jesus Movement is that it took the Sermon on the Mount seriously. While many Protestant and Catholic theologians during Christendom had so nuanced the Sermon on the Mount that it had become pedestrian and prosaic, a bunch of long-haired Jesus freaks were realizing that the Sermon on the Mount was thrilling, demanding, and dangerous as dynamite. The Jesus Movement was making Jesus revolutionary again. Indeed a common Jesus Movement motif was to represent Jesus as a kind of outlaw. This was a popular poster at the time:

If you are inclined to dismiss this as just another example of Christian kitsch, I would urge you not to. While there was obviously an element of playfulness in this poster, it actually made a serious point — a point the Jesus Movement had a correct instinct about. The Jesus of the Gospels is far more suited for an F.B.I. Wanted poster than for being the poster child of American values. While the historical Jesus certainly wasn’t a hippie, he was obviously dangerous and subversive. After all, Rome didn’t crucify people for extolling civic virtues and pledging allegiance to the empire. In announcing and enacting the kingdom of God, Jesus was countercultural and counter-imperial. This is why Jesus was crucified. His crime was claiming to be a king who had not been installed by Caesar.

The counterculture nature of the kingdom of God was a chief characteristic of the Jesus Movement — both the original one and the one that swept America in the 1970s. The early Christians of the catacombs knew that in following Jesus they would often be in opposition to the values that the Roman elite and the Roman legions stood for. And those of us at the 1970s Catacombs knew that what Jesus represented did not have an easy fit with the materialism and militarism of American culture. If anything, what Jesus taught was an out-and-out repudiation of American materialism and militarism. The Jesus Movement was no longer content with the docile and domesticated sermons of Mayberry. We weren’t interested in making Jesus safe and palatable for suburban consumers. We knew that Jesus was radical and that his message was revolutionary. We weren’t being countercultural to be avant-garde, we were being countercultural because the gospel demanded it! We weren’t being countercultural to imitate hippies, we were being countercultural to imitate Jesus!

Forty years later when I read Larry Hurtado’s Destroyer of the gods: Early Christian Distinctiveness in the Roman World and Alan Kreider’s The Patient Ferment of the Early Church: The Improbable Rise of Christianity in the Roman Empire, both attempts at capturing the ethos and praxis of the early church, I was surprised at how often what these scholars had to say about pre-Constantine Christianity called to mind memories from the Jesus Movement. Like the early church that I read about in the books of Hurtado and Kreider, we too had an almost fanatical obsession with Jesus, a clear disdain for materialism, a Sermon on the Mount-inspired opposition to war, a penchant for communal life, and a deep ambivalence toward political parties. In following Jesus we knew we were going against the grain of post-WWII American assumptions. In a word, we were countercultural.

In a culture that venerates materialism and militarism the only way to truly follow Jesus is to be countercultural. Sure, the prosperity gospel extols materialism and the religious right celebrates militarism, but these are nothing but attempts to smuggle the idols of Mammon and Mars into Christianity. A synchronistic religion that attempts to amalgamate Jesus and American values may be popular, but it’s unfaithful to the Spirit who calls the people of God out of Babylon. The writer of Revelation called the Christians of the first century catacombs away from the idolatrous seduction of empire with these provocative words—

Fallen, fallen is Babylon the great!

It has become a dwelling place of demons,

a haunt of every foul spirit,

a haunt of every foul bird,

a haunt of every foul and hateful beast.

For all the nations have drunk

of the wine of her fornication,

and the kings of the earth have committed fornication with her,

and the merchants of the earth have grown rich from the power of her

luxury. …

Come out of her, my people,

so that you do not partake in her sins,

and so that you do not share in her plagues;

for her sins are heaped high as heaven,

and God has remembered her iniquities.

(Revelation 18:2–5)

John of Patmos knew that for Christians living in the Roman Empire, faithfulness to Jesus meant they had to be deeply, even dangerously, countercultural. There was simply no way for a first-century Christian to be comfortable with Rome and faithful to Jesus. You had to choose one or the other. In the Jesus Movement of the 1970s — though we didn’t know how to properly read Revelation as a prophetic critique of the Roman Empire (and thus a prophetic critique of all empires) — we did know that following the Lamb required us to be countercultural Christians. When we said, “One Way!” (the rallying slogan of the Jesus Movement), we meant that Jesus was the only way to life, and we instinctively knew that it was incompatible with the American way of materialism, militarism, and individualism. And so we joyfully embraced a faith that was bracingly countercultural.

But we were so very young.

As it turned out most of us were not very well equipped to resist the gradual slide toward the materialism of the prosperity gospel, the militarism of the religious right, and the individualism of American evangelicalism. In time most of us ceased to be countercultural Christians and instead became conventional conservative Americans with a Jesus fish on our SUV.

Through my teens and twenties I was happy to remain a counterculture “Jesus freak.” I knew that following Jesus required me to resist the dominant culture of materialism and militarism. But eventually the Jesus Movement was absorbed by the Charismatic Movement and would be slowly seduced by the siren songs coming from the prosperity gospel and the religious right. The gradual synthesis of the gospel with material prosperity and political power happened gradually enough, and with enough biblical proof-texting, to make it seem plausible. And I went along for the ride.

I went along for the ride because I had been lulled to sleep. But in my mid forties I suddenly woke up. An alarm clock had gone off in my soul. In an astonishing way I realized I was tangled up in red, white, and blue. Awakened and disturbed at how comfortable American Christianity had become with the dominant culture, I thought, how did we get here? It’s like we got on the wrong bus somewhere back down the line. We didn’t start out as radical followers of Jesus only to end up being duped by a cadre of prosperity gospel hucksters and religious right power-mongers! So I revolted and rediscovered (at great cost) the counterculture faith I first knew as a teenager. My journey away from the compromised faith of Americanism and into the richer and more radical faith I embrace today are the stories I tell in my books A Farewell To Mars and Water To Wine. Though the road back home was sometimes painful, I’ve never once regretted my decision to return to the radical roots of a counterculture Christianity. It was a decision that saved my soul. It was a costly decision, but like the pearl of great price, it was worth it.

–Postcards From Babylon, pp. 3–9

BZ

P.S. Do it again, Lord.