Six or Eight? On Reading the Gospels

Six or Eight? On Reading the Gospels

Brian Zahnd

Let’s think about the Transfiguration for a few minutes. The mystery of Tabor is a theological diamond mine that has yielded treasures for two thousand years. Matthew, Mark, and Luke all give an account of the Transfiguration. With a tight focus on the Transfiguration story, we read that Jesus took three disciples (Peter, James, and John) up a high mountain where his divine glory was revealed in dazzling light, and where Moses and Elijah made their anachronistic appearance. When Peter suggested a construction of three tabernacles on the holy mountain — one each for Jesus, Moses, and Elijah — the idea was rebuked by the voice of God saying, “This is my beloved Son. Listen to him!” After these heavenly words, the three disciples no longer saw Moses and Elijah, but only Jesus. From this rich passage we see that the Law and the Prophets are fulfilled in Christ and that only Jesus is the perfect Word of God. The disciples are told to listen to the beloved Son because Jesus is what God has to say. This is the story of the Transfiguration in tight focus.

If we pull out a little wider, we discover a broader narrative arc. In the region of Caesarea Philippi, Peter made his confession that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of the living God. Then, for the first time, Jesus foretold his death and resurrection. When Peter attempted to dissuade Jesus from a mission that would lead to his crucifixion, he was sternly rebuked. Jesus then called all his followers to a cross-centered discipleship, concluding his discourse by saying, “there are some standing here who will not taste death before they see the kingdom of God present with power.” What happens next in the synoptics’ narrative arc is extremely important. Matthew, Mark, and Luke all go immediately into the Transfiguration story. In other words, the Transfiguration is when some of the disciples (Peter, James, and John) saw the eschatological vision of kingdom come present in the glorified Christ.

But now let’s zero in on a particular detail. Matthew and Mark say the transfiguration occurred six days after Peter’s confession, while Luke says it was eight days later. Six or eight? Which is it? For those who have been schooled in a modern reading of the Gospels, whether in fundamentalism or in higher criticism, this creates a problem. For modern fundamentalists committed to inerrant biblicism this necessitates various convoluted explanations. The modern textual critics, on the other hand, see nothing but a discrepancy among the synoptics that they are more than happy to point out. Yet both are making the mistake of reading the Gospels as a kind of journalism. The Gospel writers are not modern journalists — they are creative theologians. They consciously and creatively craft their stories in order to shape our theological imagination.

For example, Matthew, Mark, and Luke all place the cleansing of the Temple in Jerusalem during Jesus’ final week, while John places it at the beginning of Jesus’ ministry immediately following turning the water to wine in Cana of Galilee. Those who read the Gospels in the same way they read modern journalism will conclude that either John is wrong in his historical chronology or, as I’ve heard some claim, Jesus cleansed the Temple twice. Yet if we read John, not as a journalist, but as an artist engaged in theopoetics, we see something different. John places the making of wine in Cana and the making of a whip in Jerusalem in stark juxtaposition to reveal a theological point: The one who brings the kingdom of God prolongs a party but shuts down religious hucksterism. The finest wine and a braided whip reveal the joy and judgment of kingdom come. John the Evangelist is far more interested in creative theology than historic chronology.

So what about six and eight? Mark places the Transfiguration six days after Peter’s confession and Matthew follows suit. Six days as in the sixth day — Sunday, Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday. Mark and Matthew want to associate the coming of the kingdom with the crucifixion on Good Friday. Amen. The glory of the kingdom does indeed come through the cross. Yet Luke does something different. When Luke writes his Gospel sometime after Mark and Matthew, he is aware that his predecessors say, “six days later,” thus connecting the glory of the kingdom with the crucifixion. Luke knows this is true, but he wants to add an additional theological move, so he says “eight days later,” as in the eighth day — the day of resurrection and new creation. Brilliant!

Luke is not saying, “Well, I’ve done my own investigative inquiry into the matter and have discovered that the Transfiguration was, in fact, eight days after Peter’s confession.” Of course, that’s not what Luke is doing! If it’s just a matter of six or eight days between two events, who cares? What Luke is doing is engaging playfully with what Mark has already done. Luke, in effect, says, “Let’s also connect the coming of the kingdom with resurrection” — an entirely legitimate theological move. We cannot understand the Paschal Mystery unless we keep Good Friday and Easter Sunday together. The crucifixion and the resurrection are only understood in the light of one another. The inauguration of the kingdom of God is only perceived if we hold the sixth and eighth days in tandem. Luke plays off Mark in a very subtle way to lead us deeper into the Paschal Mystery. Again we see that the Evangelists are not journalists, they are theological artists, and we need to read them as such.

Reading premodern spiritual texts with a modern empiricist mind will obscure what we are meant to see. A fundamentalist reading of the Gospels will lead us down bewildering blind alleys. A historical-critical reading of the Gospels will only get us so far before it too reaches a dead end. It’s the spiritual-mystical reading of the Gospels as inspired theopoetics that will lead us ever deeper into the Paschal Mystery.

So, six or eight? Yes!

BZ

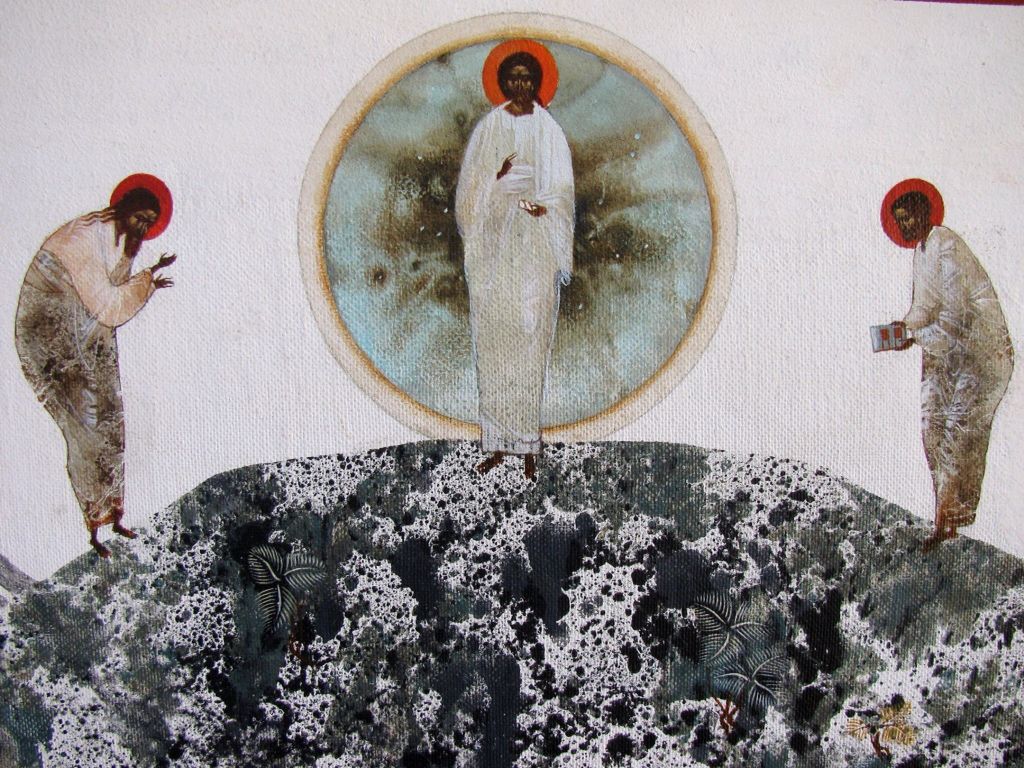

(The artwork is Transfiguration by Ivanka Demchuk.)