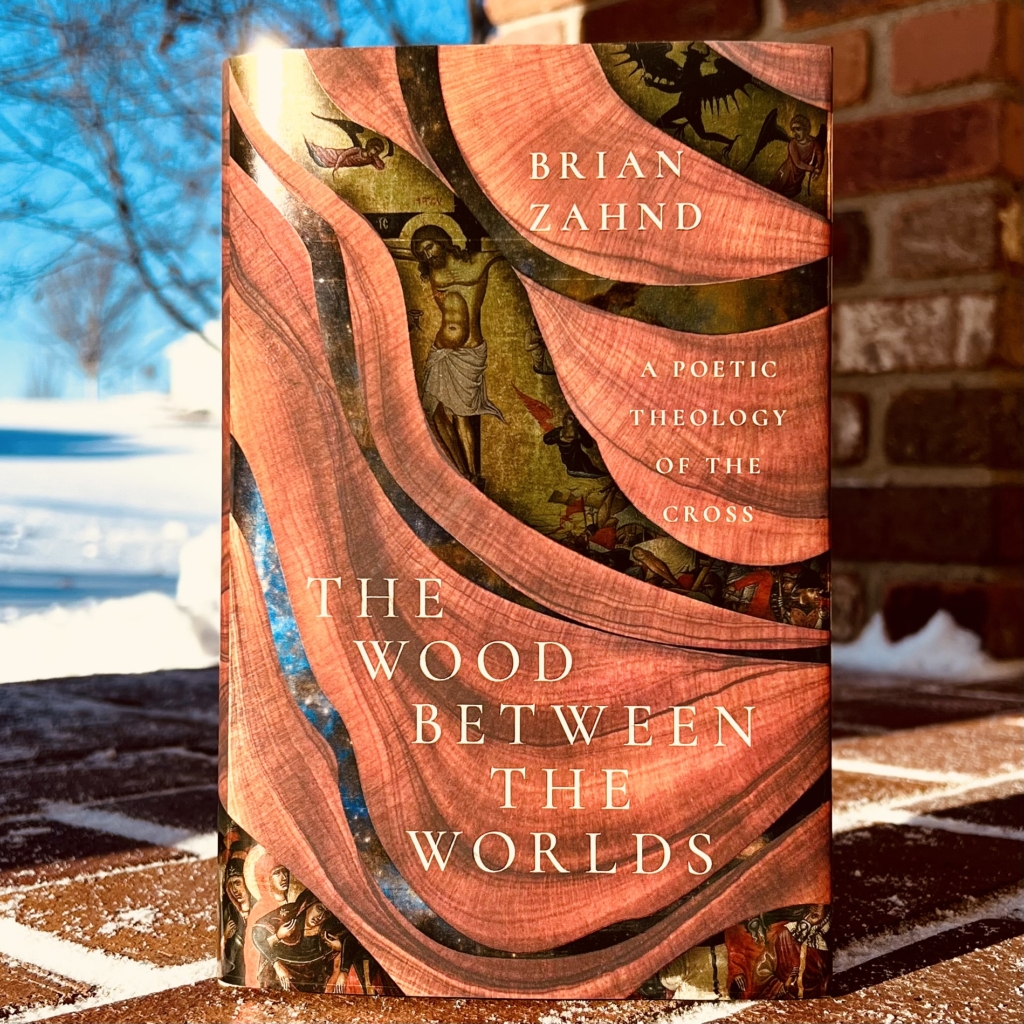

The Wood Between the Worlds

The Wood Between the Worlds releases February 6 — just in time for Lent. This is the Prelude to the book.

PRELUDE

I DARE TO WRITE ABOUT GOD, which is, admittedly, an audacious undertaking. That a bit of sentient soil would venture to say something about the nature of the ineffable Eternal must seem like the most absurd of fool’s errands. And yet I venture. I cannot help myself. The depth of my fascination with the One who is the answer to the question of why there is something instead of nothing makes it impossible for me to remain silent on the subject. I sympathize with King David when he said, “While I mused, the fire burned; then I spoke with my tongue” (Ps 39:3). And when I dare to speak about God, I do so not as the idly curious but as a reverent worshiper. I seek to understand God, not as a cold and dispassionate scientist — a God-ologist, if you will — but as one who prays, worships, and kneels before his maker.

In seeking to understand God, I am not starting from square one — far from it. Theologically, I am not tasked with harnessing fire or inventing the wheel. I am the heir of a venerable theological tradition. I am among the grateful recipients of received revelation that has been passed down for millennia. I am working from the sacred text that is the Jewish and Christian scriptures. In daring to write about God I do so with the language given to us in the Bible. I can truthfully say that my thinking is saturated in Scripture — the Bible is my primary vocabulary. Yet as essential as Scripture is, to say that the Bible clearly reveals the nature of God is to severely oversimplify the matter.

The Bible is a sprawling collection of texts that are often unwieldy and difficult to interpret. While some may speak glibly of the alleged perspicuity of Scripture, nevertheless we must acknowledge the uncomfortable reality of what Christian Smith has called “pervasive interpretive pluralism.” In other words, no matter how ardently we hold to the inspiration of Scripture and insist on its clarity, the text still has to be interpreted, and there is no denying that we are far from universal agreement on biblical interpretation. Thus it behooves us to approach the task of theological interpretation with a good deal of humility.

In seeking to interpret the biblical text with a goal of gaining insight into the nature of God, we need a way of positioning ourselves within Scripture. We need to locate an interpretive center — a focal point from which we can interpret the rest of the Bible. We need to locate the heart of the Bible. As a Christian, I have a ready, and, what seems to me, obvious location for the heart of the Bible: the cross. In the Christian gospel, everything leads to the cross and proceeds from it.

If the Bible is ultimately the grand saga of human redemption through divine intervention, the crucifixion of Jesus Christ is literally the crux of the story. The cross is the axis upon which the Biblical story turns. Who is God? God is the one who was crucified between two criminals on Good Friday. Hints at the nature of God are subsumed into a full unveiling of the divine nature at Golgotha. On Good Friday the true nature of God is on full display in Jesus of Nazareth crucified. God is the crucified one. And yet, nothing is more central to the theological vocation than interpreting the meaning of God as revealed in the crucified Christ. Theologians must gather worshipfully around the cross of Christ and speak from there. All that can truthfully be said about God is somehow present at the cross.

Yet I suspect that what can be said about God revealed in the crucified Christ is as infinite as God’s own being. Though we can begin talking about the meaning of the cross, we can never conclude the conversation. The four living creatures around the throne of God who day and night sing, “Holy, holy, holy, / the Lord God the Almighty, / who was and is and is to come” (Rev 4:8), are not automatons on infinite repeat, but angels granted an infinite series of glimpses into the ever-unfolding glory of God. Every eruption of their thrice-holy adoration is a reflexive response to a new glimpse of God’s glory. How the seraphim gather around the throne of God is how theologians should gather around the cross of Christ.

The meaning of the cross is not singular, but kaleidoscopic. Each turn of a kaleidoscope reveals a new geometric image. This is how we must approach our interpretation of the cross — through the eyepiece of a theological kaleidoscope. That the word kaleidoscope is a Greek word meaning “beautiful form” makes this all the more apropos. I believe it is safe to assume there are an infinite number of ways of viewing the cross of Christ as the beautiful form that saves the world. In this book I seek to share some of the beautiful forms I see as I gaze upon the cross through my theological kaleidoscope.

Then there is the matter of how to speak of what is seen through the theological kaleidoscope. Not all language is the same. Though in modernity we have a penchant for technical prose when engaging in theological conversation, earlier ages — and the Bible itself — have a fondness for the less precise, but also less limiting language of poetry. Theopoetics is, in part, an attempt to speak of the divine in more poetic language. It is an attempt to rise above the dull and prosaic world of matter-of-fact dogma that tends to shut down further conversation. If in this book I occasionally veer away from prose to employ slightly more poetic language in how I see the cross, this should not be regarded as fanciful, but as the best recourse I could find to describe the truth I believe the Spirit is helping me to see. It’s an invitation to consider something new. With that, let us begin what I hope will be a kaleidoscopic and theopoetic conversation about the wood between the worlds.

Advent 2022.